Defining Divinity is a project by Rising Lai (TW) and Lisette Alberti (NL), focussing on Dutch East India Company (VOC) personnel who were deified into the Taoist divine system – their legends passed down from generation to generation. This project explores the atypical heritage of these VOC Gods.

「神性之定義」由賴思穎(臺灣) 與Lisette Alberti (荷蘭) 共同發起。在臺灣,有些道教神祇相傳為荷蘭東印度公司(VOC) 人員-祂們的傳說,世代相傳於地方。本專案深入探索這些荷蘭人神祇,以及其所代表的非典型文化遺產。

From 1624 until 1662, the Dutch East India Company (VOC) colonized the southwestern coast of Taiwan.

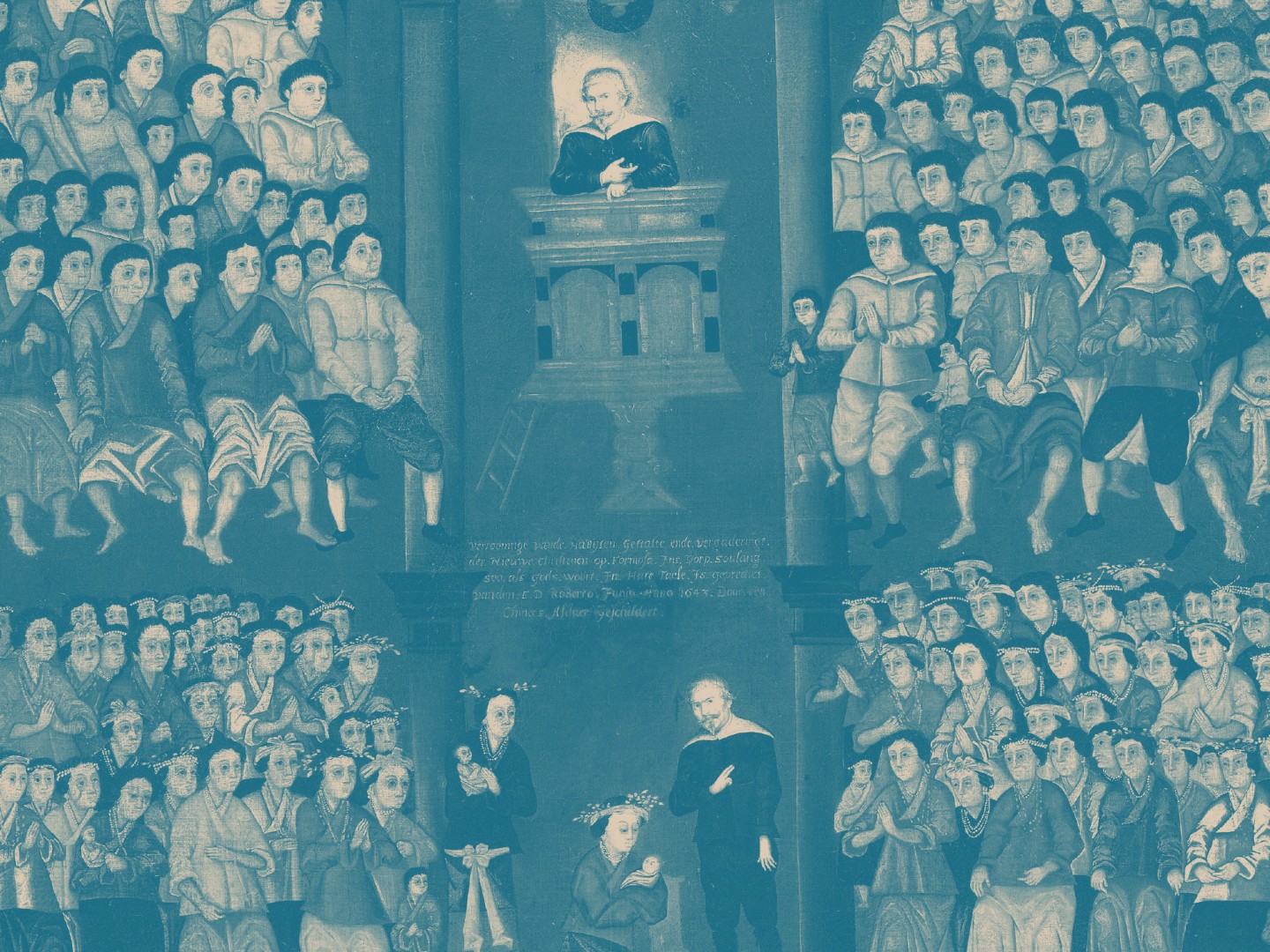

Some VOC'ers were deified into the Taoist religion, leaving a lasting trace of the colonization.

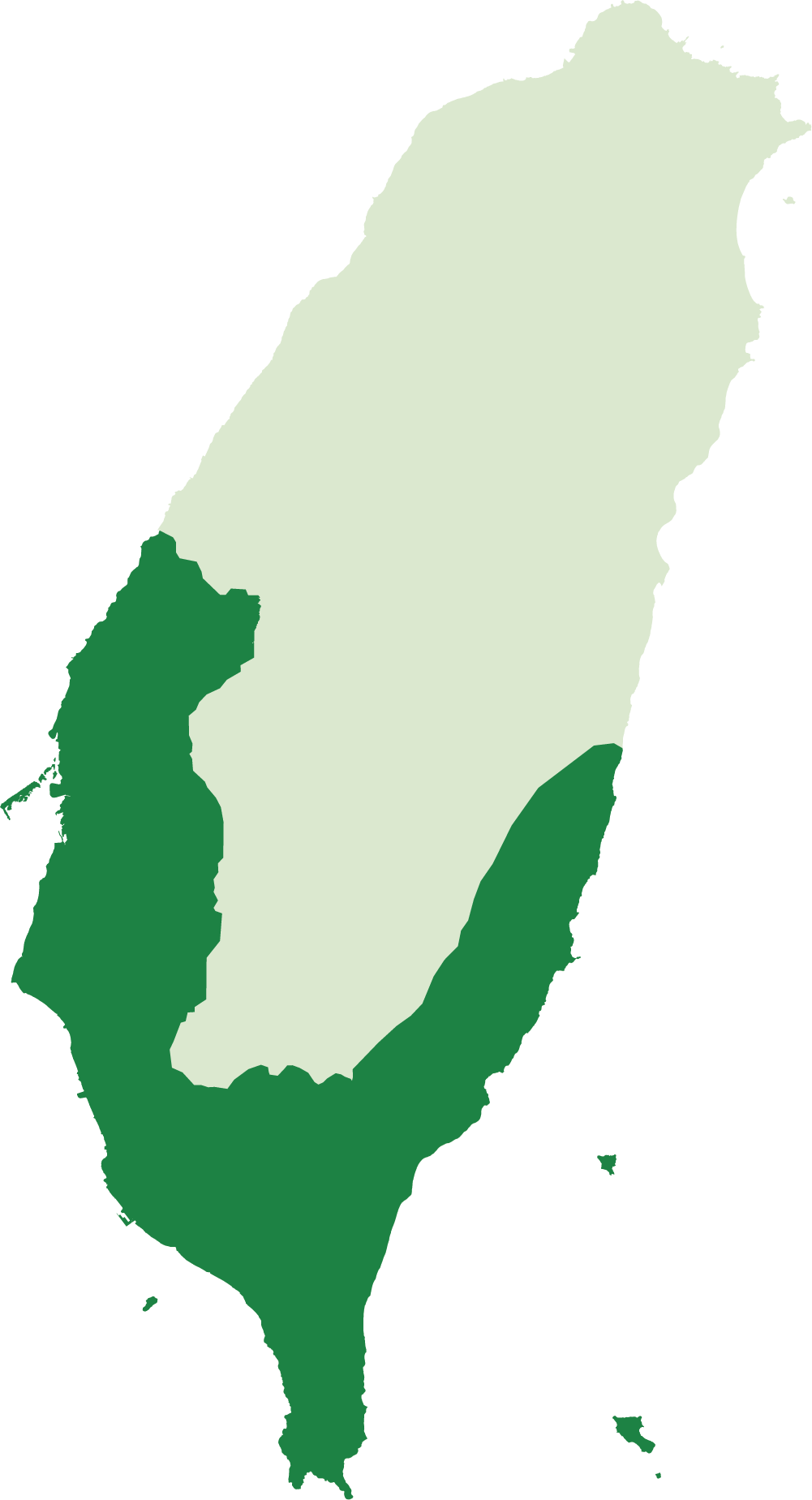

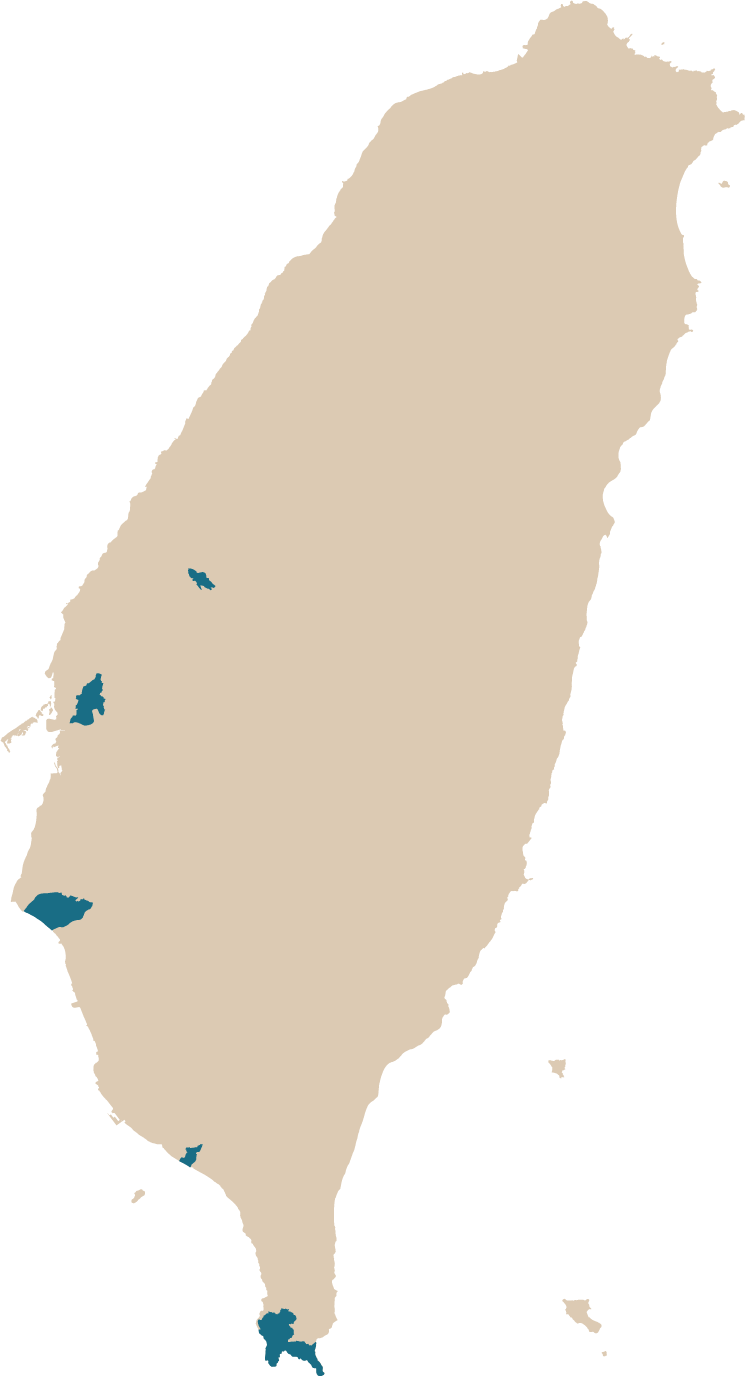

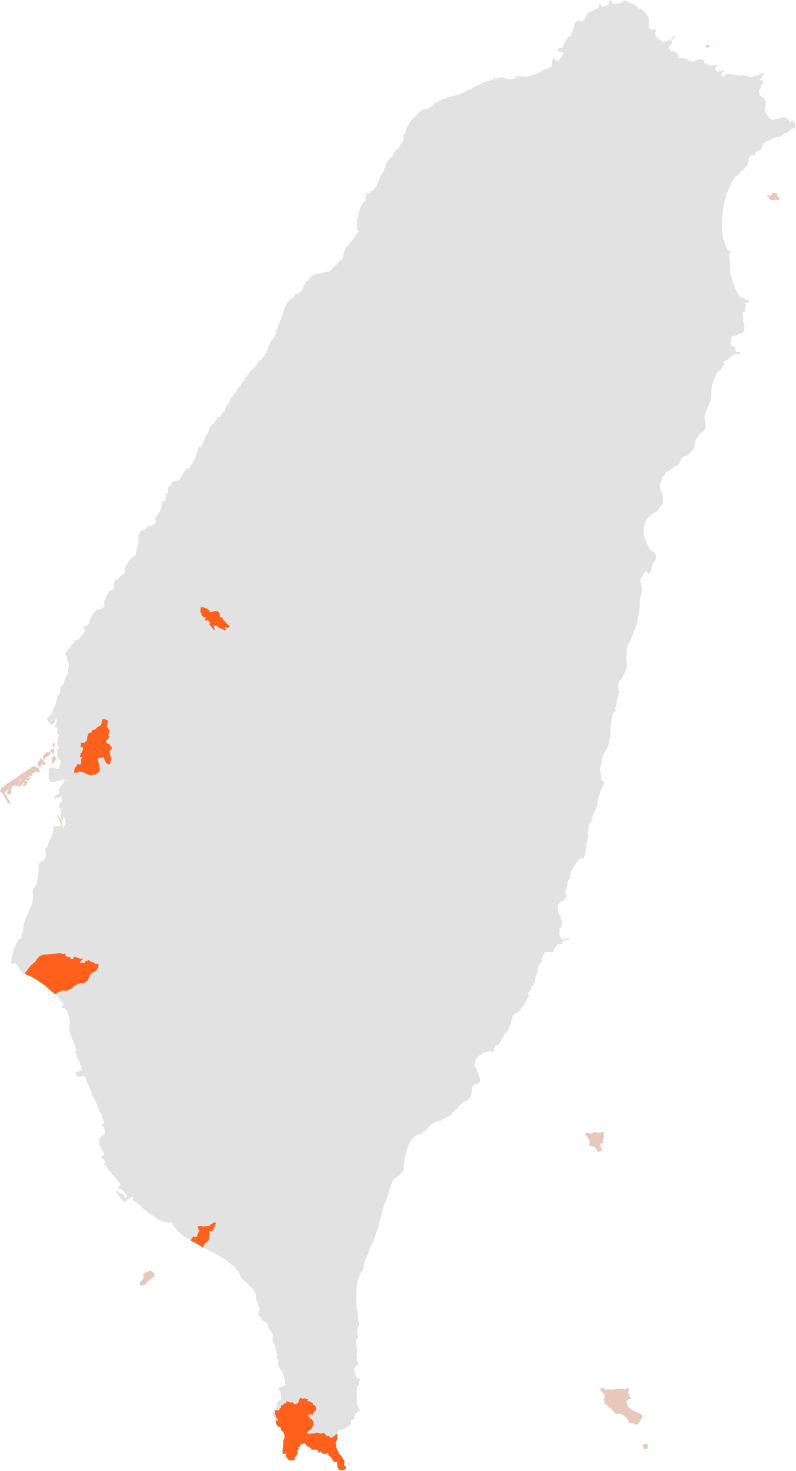

Areas controlled by the VOC

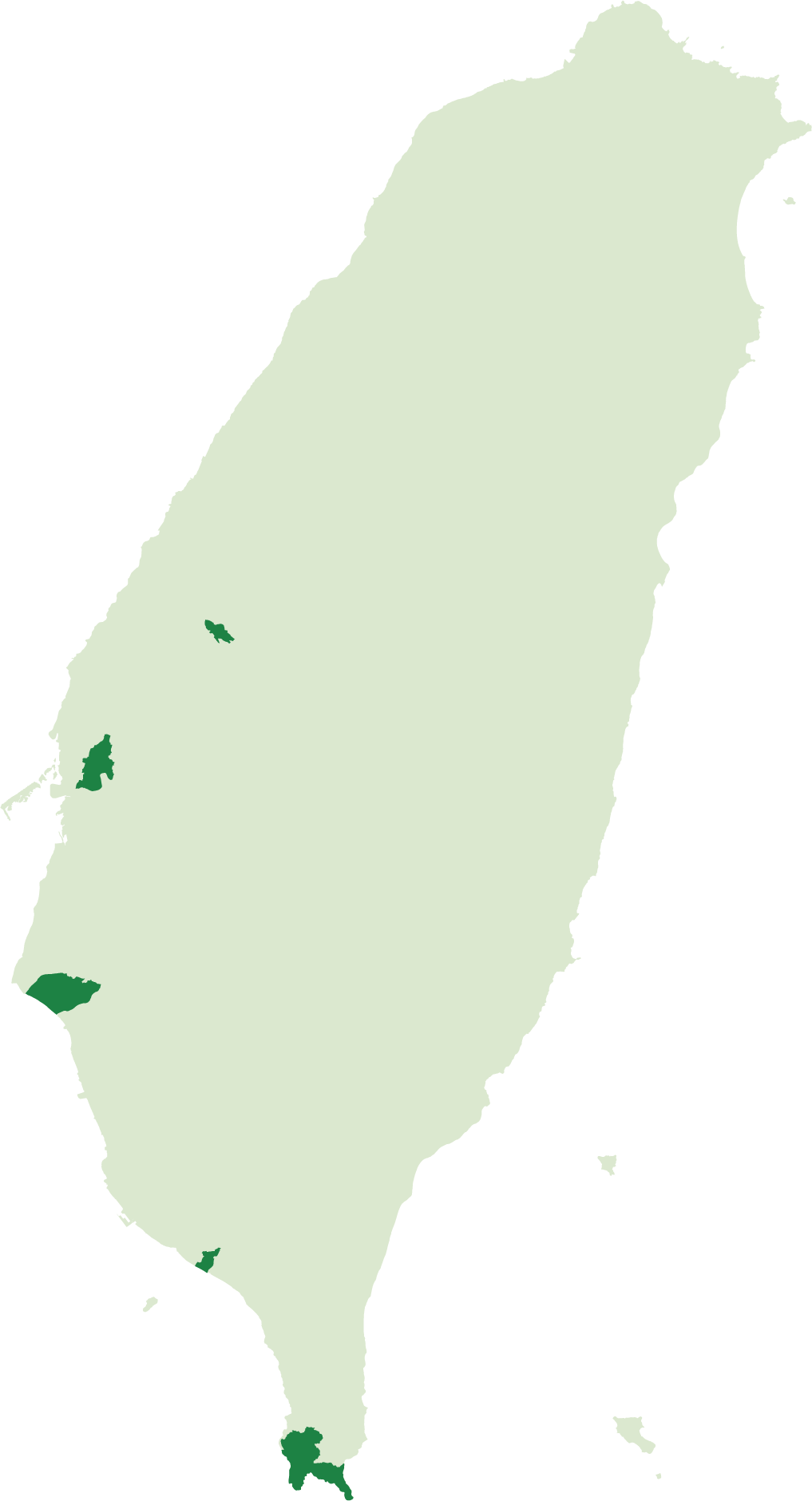

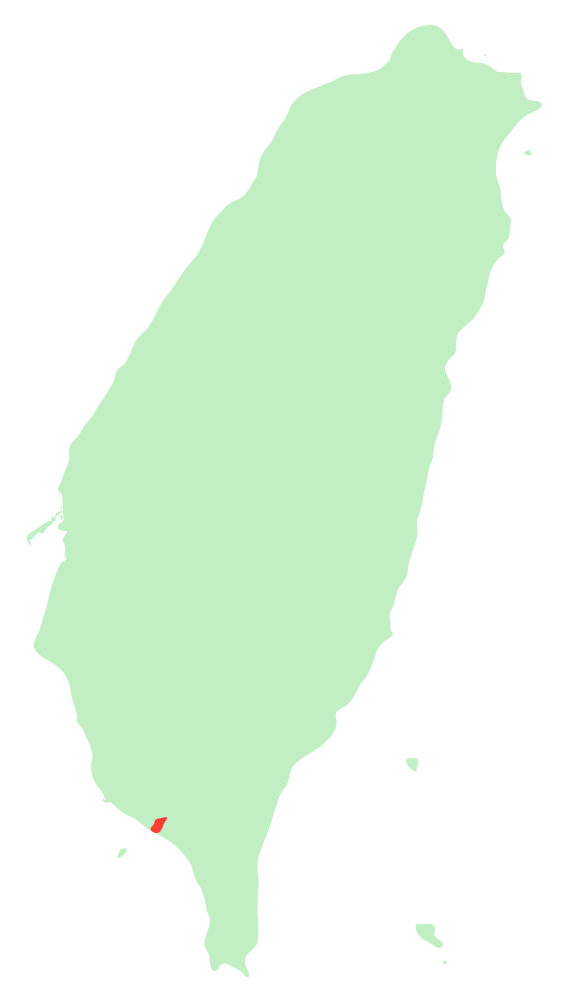

Leo is one of the Taoist Gods worshiped by the residents of Shuilin Township, Yunlin County, in midwest Taiwan.

The residents see them as a guardian of the community. Legend has it that Leo was a Dutch general who came to Taiwan during the VOC period.

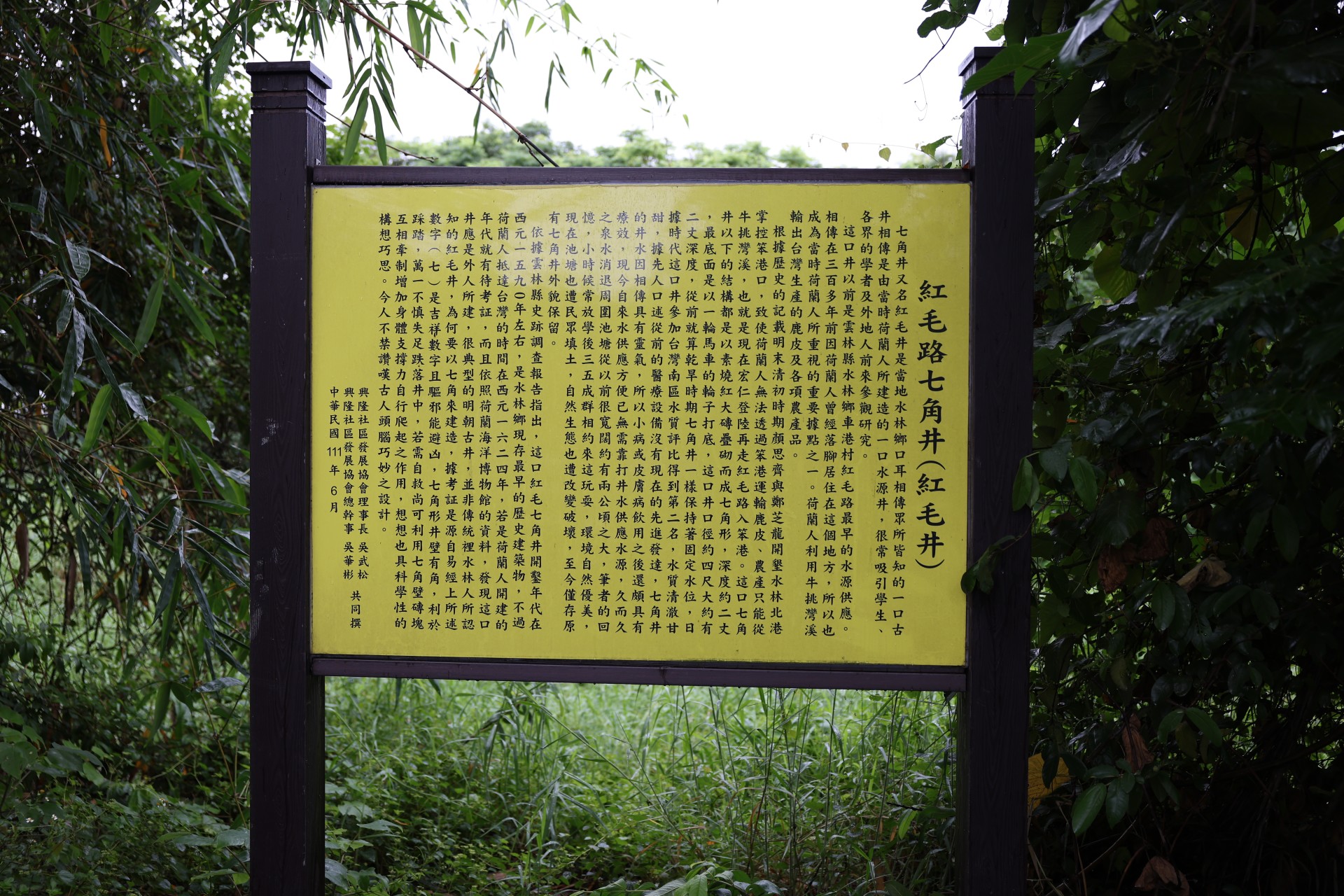

According to archaeological reports, this well was dug around 1590. However, the Dutch arrived in Taiwan in 1624.

According to information from the Dutch National Maritime Museum, this well was thus built by someone else. Its style corresponds to the typical style of the Ming Dynasty.

Archaeological history doesn't affect the Gods' histories. The religious Taoist ontological reality co-exists with the material reality.

The VOC arrived in 1624 to the southwestern coast of Taiwan. The Dutch built Fort Zeelandia in Tainan, establishing their main colonial stronghold.

Through the VOC, Taiwan became an important point of international trade for the region.

Many Taiwanese consider the VOC colonization as Taiwan's entry into the international community - emphasizing the importance of its ports to international trade in the region.

In many Taiwanese history books today, the VOC colonization marks the beginning of written Taiwanese history. Many remember it as a time of progress and wealth.

The VOC Gods are a surprising legacy of the VOC era, given the widespread violence it inflicted on indigenous communities in pursuit of its colonial and exploitative ambitions.

The Siraya people of southwestern Taiwan initially traded with the VOC, but the Dutch quickly started imposing severe taxes and forced labor. The VOC's violent attempts to convert the Siraya and alter their agricultural practices only deepened resistance, leading to an escalation of violence by the Dutch. The violent impact of the VOC's rule has left a lasting mark on the Siraya community.

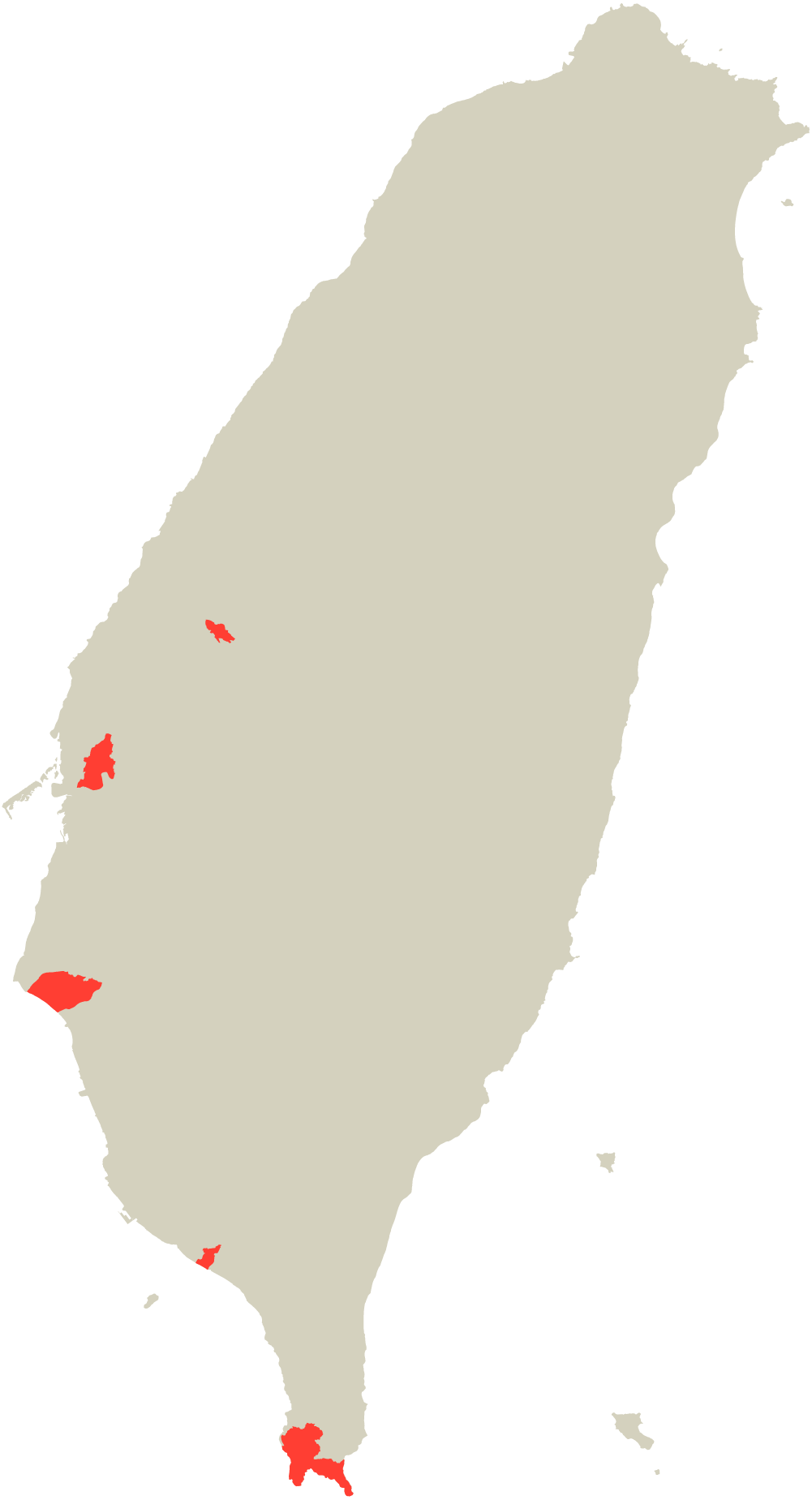

Indigenous communities continue to be marginalized, enabling the wider society to overlook their suffering under VOC rule. Currently, only 2.5% of Taiwan's total population is recognized as indigenous.

The VOC Gods' temples reflect the history of the current majority, but the indigenous population has a different story to tell.

In the stories of the VOC Gods, "Dutch" functions as a concept that recognises foreignness instead of realness. "Dutch" does not refer to specific VOC'ers, but rather to everyone who is the Other from the view of Han Taiwanese.

The more recent Taiwanese history of the White Terror shows us that history textbooks are always written by the hegemon - leading to an imposed, but fraught, political unity often necessarily enforced by violence.

The White Terror underscores the power of history-telling as a tool. This period highlights the need for a Taiwan-centered, multilingual narrative that respects diverse voices in the present day, especially within the complex relationship between Taiwan and China.

Taiwan's democratization in 1996 marked a significant milestone with its first direct presidential election, solidifying its transition from authoritarian rule to a democracy.

Driven by China's imperialistic ambitions to assert control over what it considers a renegade province, China's authoritarian regime adamantly opposes Taiwan's democratic governance and continues to employ coercive measures and threats of military force to intimidate and isolate Taiwan.

Are the VOC Gods a tool to reappropriate one's own history from colonizing powers, both past and present?

The parallel truthmaking of Taoism shows us the importance of plurality and nuance in the telling of history. It urges us to apply the Taoist ontology to create space for multiplicity, nuance and plurality.

History is complex and should leave space for multiple narratives, experiences and nuances.

Legend has it that Lady Pan might be a Dutch combat medic, a missionary. Lady Pan might also be a female priest of Makato people. Lady Pan is an iteration of Mazu for the Han Taiwanese people. Most likely, Lady Pan is a doctor from China, according to the local community.

The belief that is centered on Lady Pan could be traced back to multiple folkloric origins. This multiplicity is embraced within the religious practice of her worshippers, because there is an acceptance of diversity without the need to rationally understand the co-existing stories of origin.